Vascular tissue constitutes one of the most fundamental and defining features of higher plants, enabling the transport of water, minerals, and organic nutrients throughout the organism and thereby supporting larger body sizes, increased complexity, and diverse ecological strategies. Present in vascular plants (Tracheophyta), vascular tissue systems—comprising xylem and phloem—represent integrated networks of specialized cells and supporting structures that coordinate long-distance conduction, mechanical support, storage, and developmental signaling.

This article examines vascular tissue comprehensively: its historical discovery and classification, cellular composition and anatomical organization, mechanisms of transport, developmental origin and patterning, physiological regulation and responses to environmental conditions, evolutionary significance, and applied aspects in agriculture, forestry, and plant biotechnology.

Historical Background and Conceptual Framework

The recognition of distinct conducting tissues in plants emerged gradually as microscopy and histological techniques improved in the 17th–19th centuries. Early botanists observed strands within stems and roots that appeared to connect leaves with roots; subsequent staining and sectioning methods differentiated tissues based on cell wall thickness, presence or absence of protoplasm, and lumen characteristics. In the 19th century, the terms xylem and phloem were adopted to distinguish tissues primarily involved in water/mineral conduction and organic solute transport, respectively. The concept of the vascular bundle—a composite unit containing both xylem and phloem, often arranged in concentric or collateral patterns—became central for describing stem, root, and leaf vascular organization across taxa.

Gross Organization: Vascular Systems and Plant Body Plans

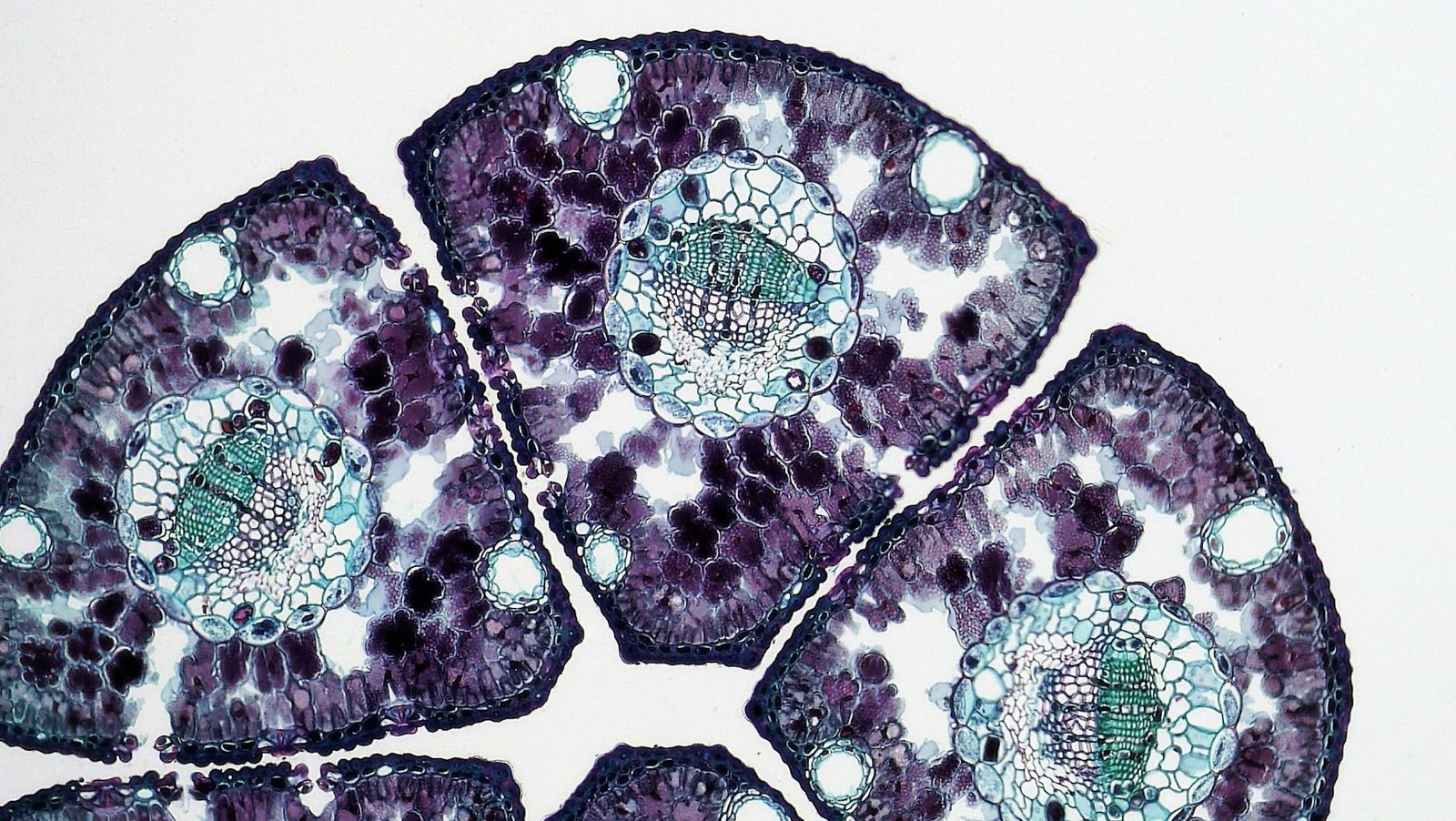

Vascular tissue is organized into continuous strands or bundles that integrate the entire plant body. In stems and roots, vascular tissues form distinct patterns reflective of phylogeny and developmental constraints. For instance, in many angiosperms the stem cross-section exhibits collateral vascular bundles with xylem oriented toward the center and phloem toward the periphery; in eudicots these bundles are typically arranged in a ring, facilitating the formation of a vascular cambium and secondary growth, whereas in monocots vascular bundles are scattered through the ground tissue, usually precluding extensive secondary thickening. The root presents an alternate arrangement—xylem often forming a central core (a xylem pole pattern) with phloem occupying interspaces—optimized for radial transport from absorptive root hairs to the shoot.

Leaves possess vascular tissues organized into veins, which form hierarchical networks from major midribs to minor vein orders; this venation supports distribution of water and nutrients, mechanical reinforcement, and efficient retrieval or export of photosynthates. The vascular cambium, when present, generates secondary xylem (wood) inward and secondary phloem outward, enabling perennial growth and the accumulation of structural support and conductive capacity.

Cellular Composition and Structural Specializations

Xylem

Xylem functions primarily in the unidirectional transport of water and dissolved inorganic ions from roots to aerial parts, and in mechanical support. Its major constituents include tracheary elements (tracheids and vessel elements), xylem parenchyma, and fibers.

- Tracheids: Long, tapering cells with lignified secondary walls and bordered pits that facilitate water movement between adjacent cells while provisionally limiting air spread. Tracheids are the principal conductive cells in gymnosperms and many pteridophytes.

- Vessel elements: Shorter, wider cells aligned end-to-end to form continuous vessels; end walls are perforated or entirely dissolved to reduce resistance to axial flow. Vessel elements are predominant in most angiosperms and are associated with higher hydraulic conductivity but potentially greater vulnerability to embolism.

- Xylem parenchyma: Living cells that store carbohydrates and assist in lateral transport, repair, and refilling of embolized conduits.

- Fibers and sclerenchyma: Provide tensile strength and support; these cells have heavily lignified walls.

Xylem secondary walls exhibit characteristic patterns—annular, helical, scalariform, or pitted—related to growth dynamics and mechanical demands. Lignification of walls confers rigidity and decay resistance, key features underlying secondary xylem’s functional integration as wood.

Phloem

Phloem is responsible for bidirectional translocation of organic solutes (principally sucrose), signaling molecules, and some hormones. Its principal elements include sieve elements, companion cells (in seed plants), phloem parenchyma, and phloem fibers.

- Sieve elements: Specialized conductive cells lacking a nucleus at maturity and possessing sieve plates at their end walls, which facilitate cytoplasmic continuity and mass flow. In angiosperms, sieve-tube elements are connected end-to-end to form sieve tubes; in gymnosperms, sieve cells perform the analogous function but lack companion cells.

- Companion cells: Parenchymatous cells closely associated with sieve-tube elements in angiosperms; they are metabolically active and provide ATP, proteins, and regulatory molecules required for sieve-element function via plasmodesmatal connections.

- Phloem parenchyma: Storage and lateral transport.

- Phloem fibers: Provide mechanical support and protection.

Sieve plates can vary in morphology (simple vs compound) and influence resistance to flow. The maintenance of turgor, loading/unloading dynamics, and regulated occlusion (e.g., by callose deposition or P-protein plugging following injury) are essential to phloem integrity.

Mechanisms of Transport

Xylem Transport: Cohesion-Tension Theory

The predominant model explaining long-distance xylem transport is the cohesion-tension theory. Evaporation of water from mesophyll cell walls in the leaf apoplast (transpiration) generates a negative pressure (tension) that is transmitted through the continuous water column in xylem conduits. Cohesive forces between water molecules (hydrogen bonding) and adhesive forces between water and hydrophilic cell walls maintain continuity.

Root water uptake driven by soil water potential replenishes the column, producing a net upward flow that can deliver water to tall trees over considerable vertical distances. Hydraulic conductivity is influenced by conduit diameter, vessel length, pit structure, and the presence of embolisms. Vulnerability to cavitation (formation of gas-filled emboli leading to hydraulic failure) depends on conduit anatomy and environmental stressors such as drought, freeze-thaw cycles, or pathogen-induced cavitation.

Phloem Transport: Pressure-Flow Hypothesis

Phloem translocation is commonly described by the pressure-flow (Münch) hypothesis. Sugars produced in photosynthetic “source” tissues (e.g., mature leaves) are actively loaded into sieve elements, increasing osmotic potential and drawing water from adjacent xylem into the phloem, thereby generating elevated turgor pressure at the source. At sinks (growing tissues, roots, storage organs), unloading of sugars and conversion or utilization reduces solute concentration, lowering turgor. The resulting pressure differential drives bulk flow of phloem sap from source to sink.

Loading and unloading mechanisms vary—phloem loading may be apoplastic (active transport across membranes) or symplastic (via plasmodesmata), with implications for energy use, phloem sap composition, and ecological strategies. While the pressure-flow model captures large-scale behavior, additional regulatory layers—membrane transporters, cytoskeleton dynamics, and signaling—modulate phloem function.

Developmental Origin and Patterning

Vascular tissues arise from meristematic precursors. Primary vascular tissues differentiate from procambium during primary growth, under the influence of positional cues, auxin gradients, and interplay with other developmental regulators. Auxin transport via PIN and AUX/LAX transporter families establishes maxima that prefigure vascular strand formation; canalization models explain how auxin flux becomes concentrated into narrow strands that differentiate into procambial cells. The activity of transcription factors (e.g., HD-ZIP III, KANADI) and peptide signaling pathways contributes to vascular patterning and polarity (e.g., determining xylem vs phloem identity and the bilateral symmetry of leaf vasculature).

Secondary growth in woody species involves the vascular cambium, a lateral meristem that produces secondary xylem and phloem. Cambial activity is tightly regulated by hormonal signals (auxin, cytokinins), mechanical stress, seasonal cycles, and developmental programs that balance radial expansion with conduit specification. The interfascicular cambium arises between primary vascular bundles, linking them into a continuous cylinder in stems that undergo secondary thickening.

Physiological Regulation and Environmental Responses

Vascular tissues are dynamic, responsive systems integrated with plant physiology and environmental sensing. Key regulatory and adaptive processes include:

- Drought response: Under water deficit, stomatal closure limits transpiration, reducing xylem tension but also photosynthetic carbon gain. Plants may remodel root-to-shoot allocation, produce smaller conduits, or adjust phloem loading strategies to sustain hydraulic safety. Aquaporins (membrane water channels) modulate cell-level water permeability; their regulation affects both xylem refill capabilities and phloem function.

- Temperature and freeze-thaw: Freezing can provoke air-seeding or cavitation in xylem conduits. Some species mitigate this by producing narrower vessels or via embolism repair during thawing, sometimes assisted by living xylem parenchyma.

- Pathogen and herbivore attack: Vascular pathogens (e.g., Ophiostoma in Dutch elm disease, Xylella fastidiosa) compromise transport and can elicit occlusion responses. Phloem-feeding insects (aphids) exploit phloem sap and can induce complex plant defenses, including callose deposition at sieve plates, production of deterrent secondary metabolites, and alterations in phloem sap composition.

- Signaling: Vascular tissues serve as conduits for systemic signaling molecules, including hormones (auxin, abscisic acid), peptides, RNAs, and electrical signals. Phloem-mediated movement of mobile RNAs and proteins can coordinate developmental processes such as flowering, tuberization, and systemic acquired resistance.

Evolutionary Perspectives

The origin of vascular tissue was pivotal in plant evolution, enabling a transition from small, simple bryophyte-like bodies to large, structurally complex land plants. Early vascular plants (e.g., Rhyniophytes) possessed primitive conducting cells and simple branching axes; the subsequent diversification of tracheary elements, lignification mechanisms, and cambial activity facilitated the evolution of trees and forests. The appearance of vessel elements in angiosperms represented a major innovation associated with high hydraulic efficiency and diversification of ecological niches, though accompanied by trade-offs in vulnerability to embolism. Comparative anatomy across extant and fossil taxa reveals multiple independent modifications of vascular architecture, reflecting selection pressures like water availability, mechanical demands, and life history strategies.

Applied Significance

Understanding vascular tissue has substantial practical implications:

- Agriculture: Crop yield and resilience are tied to vascular efficiency—water transport capacity affects drought tolerance and stomatal behavior, while phloem transport influences carbohydrate allocation to seeds, fruits, and storage organs. Breeding and genetic engineering targeting xylem vulnerability, root hydraulic conductance, and phloem loading/unloading pathways can improve productivity under stress.

- Forestry and wood science: Secondary xylem (wood) properties—density, vessel size, ring structure—determine timber quality and utility. Knowledge of cambial dynamics aids forest management, tree breeding, and carbon sequestration strategies.

- Plant pathology: Many economically important diseases are vascular in nature. Understanding host–pathogen interactions within vascular tissues informs control strategies, diagnostic tools, and development of resistant cultivars.

- Biotechnology and synthetic biology: Manipulating vascular development has potential for altering plant form and function—engineering enhanced phloem loading for increased yield, modifying lignin biosynthesis for improved biomass processing, or creating plants with novel transport properties for phytoremediation.

Current Research Frontiers

Cutting-edge research continues to refine our understanding of vascular biology. Areas of active inquiry include:

- Molecular mechanisms of cambium initiation and maintenance, and the genetic control of wood formation.

- Fine-scale hydraulics: quantifying vulnerability to embolism at cellular-to-organ scales, and mechanisms of embolism repair.

- Phloem molecular composition: elucidating the roles of mobile RNAs, proteins, and metabolites in systemic signaling and their manipulation for crop improvement.

- Integration of mechanobiology: how mechanical forces, growth strain, and tissue stresses interact with vascular differentiation.

- Modeling whole-plant water and carbon transport under variable environmental regimes, integrating hydraulic, metabolic, and stomatal dynamics to predict responses to climate change.

Vascular tissue embodies a complex, multifunctional system central to plant life. Through specialized cells and orchestrated developmental programs, xylem and phloem accomplish the twin tasks of resource distribution and structural support, enabling terrestrial plants to grow large, colonize diverse habitats, and support complex life histories. Ongoing research into the cellular, molecular, and biophysical mechanisms governing vascular function promises to enhance our capacity to manage crops and forests, mitigate the impacts of environmental stress, and leverage plant systems for sustainable solutions. A deepened understanding of vascular tissue thus remains both a foundational scientific pursuit and a practical imperative for addressing ecological and agricultural challenges in the Anthropocene.

Discover more from Decroly Education Centre - DEDUC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.