Effect size is a fundamental concept in statistics that quantifies the magnitude of a phenomenon, relationship, or difference observed in data. Unlike p-values, which indicate whether an observed effect is unlikely to have occurred under a specified null hypothesis, effect sizes convey how large or practically meaningful that effect is. This distinction has become increasingly emphasized in fields across the social, behavioral, medical, and natural sciences because statistical significance does not equate to substantive importance. In research practice, transparent reporting of effect sizes, accompanied by confidence intervals and appropriate interpretation, is necessary for cumulative science, evidence synthesis (such as meta-analysis), and informed policy or clinical decision-making.

Defining Effect Size

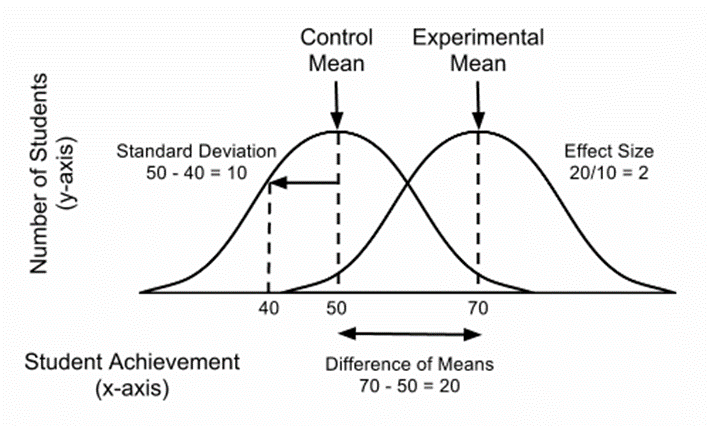

At its essence, an effect size is a standardized or unstandardized metric that measures the strength, magnitude, or practical importance of an effect. Effect sizes can be descriptive (simply reporting the observed difference or association) or standardized (rescaling that difference so it is comparable across studies with different units or measurement scales). Common types include mean differences, proportions, correlation coefficients, odds ratios, risk ratios, standardized mean differences (e.g., Cohen’s d), and measures derived for regression models (e.g., standardized regression coefficients, partial correlations, or pseudo-R^2 measures).

Unstandardized effect sizes are expressed in the original units of measurement—for instance, a treatment group’s mean systolic blood pressure is 8 mmHg lower than a control group. Such unstandardized measures are directly interpretable in applied contexts and useful when stakeholders understand the measurement units. Standardized effect sizes, by contrast, divide the raw effect by an estimate of variability (often a standard deviation) to produce a unitless index. Standardization facilitates comparison across studies, constructs, or measurement scales; however, it may obscure the clinical or policy relevance when units or variability have particular interpretations.

Common Effect Size Measures

Mean Difference

- Raw mean difference: The difference between two group means (μ1 − μ2). Useful when variables share the same units and are meaningful to stakeholders.

- Standardized mean difference: Cohen’s d, Hedges’ g, and Glass’s Δ. Cohen’s d is the difference between group means divided by the pooled standard deviation. Hedges’ g adjusts Cohen’s d for small-sample bias. Glass’s Δ uses the control group standard deviation for standardization and is sometimes preferred when treatment inflates variability.

- Interpretation conventions (e.g., Cohen’s benchmarks of 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large) are heuristics, not rules: contextual factors and domain knowledge should guide interpretation.

Correlation Coefficients

- Pearson’s r quantifies linear association between two continuous variables, ranging from −1 to +1. Squaring r (r^2) gives the proportion of variance explained.

- Spearman’s rho or Kendall’s tau are rank-based analogues used when assumptions for Pearson’s r are violated.

- Converting r to other effect-size metrics (e.g., Cohen’s d) is possible and common in meta-analysis.

Odds Ratios and Risk Ratios

- Odds ratio (OR) indicates the ratio of odds of an event in one group to the odds in another; frequently used in case-control studies and logistic regression.

- Risk ratio (relative risk) compares probabilities directly and is often more interpretable in cohort studies or randomized trials.

- Both are multiplicative effect measures; interpretation requires attention to baseline risk because a given OR can correspond to very different absolute risk differences.

Proportion Differences and Absolute Risk Reduction

- Absolute risk difference (ARR) is the difference in event rates between two groups and is directly meaningful for clinical decisions.

- Number needed to treat (NNT) is the reciprocal of ARR and expresses how many patients must receive an intervention to prevent one outcome event.

Measures for Multivariable Models

- Standardized regression coefficients: regression coefficients scaled to represent the change in standard deviations of the outcome per standard deviation change in the predictor, allowing comparison across predictors.

- Semi-partial (part) and partial correlations: quantify unique variance accounted for by a predictor controlling for others.

- Pseudo-R^2 statistics in generalized linear models provide approximate measures of explained variance, with multiple competing definitions (e.g., Cox & Snell, Nagelkerke) each having limitations.

Nonparametric and Model-Specific Measures

- For ordinal or non-normal data, rank-biserial correlation or Cliff’s delta can quantify effect magnitude.

- In survival analysis, hazard ratios convey relative event rates over time; translating hazard ratios into absolute terms often requires assumptions about baseline hazard.

Interpretation: Statistical Versus Practical Significance

A central tenet is that statistical significance and effect size address different questions. Statistical significance (often via a p-value) estimates compatibility between the observed data and a null hypothesis under a specified model and sampling process. In contrast, effect size quantifies the magnitude of the effect observed. A small effect can be highly statistically significant if sample size is large; conversely, a large but noisy effect might not reach statistical significance in a small sample. Therefore, reporting effect sizes with confidence intervals is critical:

- Confidence intervals for effect sizes provide a range of plausible values given the data and model, making uncertainty explicit.

- When intervals exclude values considered trivial for practical purposes, we have more reason to believe the effect has substantive importance.

- Equivalence testing and minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) are approaches to formalize whether an observed effect is practically meaningful or trivially small.

Context matters: domain-specific benchmarks, cost-benefit considerations, baseline risk, feasibility, and stakeholder values influence whether an effect size is meaningful. For example, a small improvement in average test scores may be consequential at population scale in education policy, whereas a similar standardized change in an individual-level biometric measure might be clinically irrelevant.

Role in Meta-Analysis and Cumulative Science

Effect sizes are indispensable in meta-analysis, where studies with different scales and designs must be synthesized. Standardized effect sizes enable aggregation, weighting by precision (often inverse variance), and estimation of pooled effects while modeling heterogeneity across studies (random-effects models). Key considerations include:

- Choosing appropriate effect-size metrics and transformations to ensure comparability (e.g., converting ORs to log-ORs, Pearson r to Fisher’s z for variance-stabilizing transformations).

- Handling study-level heterogeneity via τ^2 (between-study variance) and presenting prediction intervals that reflect the likely range of effects in future similar studies.

- Assessing publication and reporting biases, since studies with small or null effects may be underreported; effect-size distributions and funnel plots are diagnostic tools.

- Reporting both summary effect sizes and measures of heterogeneity to enable nuanced conclusions.

Computation and Estimation Issues

Estimating effect sizes involves several practical considerations:

- Sampling variability and bias: Small sample sizes inflate estimator variability and can produce biased standardized effect-size estimates; Hedges’ g corrects for small-sample bias in Cohen’s d.

- Choice of standardizer: Pooling standard deviations assumes homogeneity of variance; when variances differ substantially, Glass’s Δ or other approaches might be preferred.

- Non-independence and clustering: In clustered or longitudinal data, naive effect-size calculations ignoring dependence will misstate precision; multilevel models and cluster-robust standard errors are necessary.

- Model misspecification and confounding: In observational studies, effect sizes may reflect confounding and should be interpreted as associations rather than causal effects unless strong identification strategies are applied (e.g., randomization, instrumental variables, matching).

- Transformation and back-transformation: Some effect sizes (e.g., log-odds ratios) are estimated on transformed scales; converting them into absolute or more interpretable metrics often requires assumptions about baseline prevalence.

Communication and Reporting Best Practices

Clear, transparent reporting of effect sizes enhances reproducibility and utility of research. Recommended practices include:

- Report both effect sizes and measures of uncertainty (confidence intervals, standard errors).

- Prefer reporting absolute effects alongside relative metrics to aid interpretation (e.g., absolute risk reduction and NNT in clinical trials).

- Use standardized effect sizes for comparability across studies but accompany them with context that explains practical implications.

- Pre-specify primary effect-size metrics and minimal important differences in study protocols and registrations.

- In publications, provide sufficient detail to allow re-estimation or transformation of reported effects (e.g., means, standard deviations, sample sizes, event counts).

- Avoid overreliance on conventional heuristics (like Cohen’s small/medium/large thresholds) without domain justification.

Effect Size in Causal Inference

When the research goal is causal inference, effect sizes are interpreted as causal effects only under credible identification assumptions. Randomized controlled trials naturally permit causal interpretation of mean differences, risk differences, and other effect sizes, subject to adherence and loss to follow-up. In observational contexts, methods such as propensity score weighting, matching, regression adjustment, instrumental variables, difference-in-differences, and regression discontinuity designs aim to approximate randomization. Effect-size estimates from these methods require careful sensitivity analyses to unmeasured confounding, selection bias, and model dependence. Reporting both adjusted effect sizes and unadjusted estimates, along with diagnostics and robustness checks, helps readers assess credibility of causal claims.

Examples of Effect Size Interpretation Across Domains

- Clinical trials: A new antihypertensive reduces systolic blood pressure by 5 mmHg (95% CI: 3–7 mmHg). Whether this is clinically meaningful depends on baseline risk and guideline thresholds; even modest reductions can yield meaningful public health benefits when applied across populations.

- Education: An intervention increases standardized test scores by 0.15 standard deviations. Though small by some heuristics, cost, scalability, and cumulative effects across cohorts may justify implementation.

- Psychology: A meta-analysis finds Cohen’s d = 0.30 for a therapy’s effect on symptom reduction; reporting confidence intervals, study heterogeneity, and practical significance (e.g., remission rates) gives fuller understanding.

- Epidemiology: An exposure is associated with an odds ratio of 1.5 for a disease; translating this into absolute risk increases requires baseline incidence knowledge to assess public health impact.

Limitations and Misuse

Effect sizes are powerful but subject to misuse:

- Over-standardization: Standardized metrics can mask important distributional features; different variances across populations affect interpretation.

- Ignoring uncertainty: Point estimates without intervals mislead about precision.

- Misinterpretation of ratios: Treating ORs as risk ratios without considering baseline risk leads to overstatement of effects when outcomes are common.

- Cherry-picking: Selecting effect-size metrics or subgroups after seeing data can inflate apparent effects; pre-registration and transparent reporting mitigate this.

- Equating statistical significance with importance: A statistically significant but trivial effect can be mistaken for a meaningful finding if effect size and context are ignored.

Effect size is a central concept in statistical practice that shifts attention from mere statistical significance to the magnitude, direction, and practical relevance of findings. Proper use involves selecting appropriate effect-size measures, estimating them with rigor, reporting uncertainty, and interpreting results in substantive context. In meta-analysis and cumulative research synthesis, effect sizes enable aggregation and comparison across studies, while in causal inference they must be supported by credible identification strategies. The astute use and transparent reporting of effect sizes are essential for sound scientific inference, evidence-based decision-making, and the responsible communication of research findings.

Discover more from Decroly Education Centre - DEDUC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.