Conflict and negotiation are inevitable features of organisational life. The diversity of backgrounds, values, goals, and interests among stakeholders creates friction that managers must skillfully manage. When handled well, conflict can stimulate creativity, drive improvement, and strengthen organizational resilience. When ignored or mismanaged, conflict undermines morale, wastes resources, and damages performance. This article examines the sources of workplace conflict, defines negotiation and its types, describes the role of the negotiator, and outlines practical strategies and mechanisms—both internal and external—that organizations can use to resolve disputes and preserve cooperative capacity.

Meaning of Conflict

Conflict is a universal feature of human behavior and interaction. It arises wherever needs, interests, and goals diverge, making it an inevitable part of social and organizational life. As Dunlop (1965) observed, conflict is not an anomaly but a natural outcome of competing demands in the workplace.

🌍 Conflict in the World of Work

The workplace is fundamentally a world of needs and interests. Individuals participate in organizations for different reasons—owners seek profit, managers pursue efficiency, and employees strive for fair compensation and security. According to Jayeoba, Ayantunji, & Sholesi (2013), organizations act as need-fulfilling agents, generating and distributing resources through production processes. These activities inevitably raise questions of equity, fairness, and justice, which often become sources of tension.

👥 Stakeholders and Divergent Goals

Conflict in organizations emerges because stakeholders have different and sometimes competing goals. Jayeoba et al. (2013) identify at least nine key stakeholder groups in the workplace:

- Workers

- Workers’ unions

- Management

- Owners

- Associations of business owners

- Customers

- Government

- Retirees

- Society at large

Each of these groups derives benefits from organizational outcomes—such as products, services, salaries, profits, dividends, taxes, and social responsibility. At the same time, they share in the inconveniences and losses that conflict produces.

🍞 The Organization as a “Need-Fulfilling Agent”

In this sense, the organization can be seen as a provider of industrial resources, or “baking the industrial pie,” from which multiple stakeholders seek their share. Because the distribution of this pie rarely satisfies all parties equally, conflict becomes an inherent part of organizational dynamics.

Meaning, Types of Negotiation, and the Role of the Negotiator

Meaning of Negotiation

Negotiation—often used interchangeably with bargaining—is a lifelong, give-and-take process between interdependent parties with conflicting interests. It aims to reach agreement, defined as a concurrence of opinion or mutual understanding.

In practice, especially in collective bargaining, negotiation is far more complex than simple verbal consensus. It typically involves:

- Formal documentation of agreed terms, conditions, timelines, and consequences of default

- Ceremonial elements, such as signing agreements and making public commitments

- A symbolic declaration of peace and cooperation between parties

Negotiation is thus both a strategic process and a relational commitment to resolving disputes constructively.

🔄 Types of Negotiation (Adapted from Eze, 2004)

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Win–Lose | One dominant party achieves its goals at the expense of the other |

| Lose–Lose | Neither party achieves their objectives; both walk away dissatisfied |

| No Deal | Total disagreement; no resolution is reached |

| Compromise | Each party sacrifices some demands to reach a partial agreement |

| Win–Win | Both parties find mutually satisfying solutions through effective trade-offs |

Note: While often associated with integrative bargaining, win-win outcomes can emerge from various negotiation strategies when trust and creativity are present.

🧑💼 The Negotiator: Skills and Attributes

Negotiators are developed through experience and training, not born. They may be internal stakeholders or external experts, but must possess key competencies to succeed:

- ✅ Positive attitude and ethical disposition

- 🤝 Ability to negotiate in good faith

- 🧠 Strong memory for facts, names, and events

- 🔍 Clear understanding of dispute issues

- 💡 Creative problem-solving skills

- 🗣️ Effective and persuasive communication

- 🎯 Emotional and general intelligence

- 👁️ Perceptiveness and intuition

Successful negotiators balance assertiveness with empathy, aiming for outcomes that are both strategically sound and relationally sustainable.

Types of Bargaining Approaches

🔍 Integrative Bargaining

Integrative bargaining is a problem-solving approach where parties collaboratively confront issues, identify shared concerns, and generate mutually beneficial solutions. It is particularly effective when:

- Complex or multi-dimensional issues are involved

- There is a need to bridge misunderstandings or rebuild trust

- Long-term relationships and sustainable outcomes are desired

Examples of integrative bargaining issues include:

- Low productivity

- Declining market share

- Economic downturns

- Negotiations around redundancies, layoffs, overtime reductions, or pay adjustments

This approach fosters cooperation and can produce lasting solutions—especially when conflicts are not rooted in fundamentally opposing value systems.

⚖️ Distributive Bargaining

Distributive bargaining focuses on dividing limited resources, often resulting in a competitive, win-lose dynamic. It typically involves:

- Wage rates

- Holiday entitlements

- Overtime compensation

- Bonuses and fringe benefits

Because one party’s gain is perceived as the other’s loss, this approach can breed future conflict and tension. It is best suited for single-issue negotiations where compromise is difficult.

🛑 Conjunctive Bargaining

Conjunctive bargaining is power-based and adversarial, used when parties seek to dominate rather than collaborate. Key characteristics include:

- High concern for self, low concern for others

- Minimal cooperation and trust

- Use of coercion or pressure tactics

This approach may lead to short-term gains for one party but often results in:

- Hostility and frustration

- Loss of face for the weaker party

- Unresolved tensions and future crises

It is rarely conducive to long-term dispute resolution.

⚓ Concession Bargaining

Concession bargaining arises in economic downturns or organizational crises, where both management and workers prioritize survival. It involves:

- Mutual compromises to keep the organization afloat

- Temporary sacrifices in promotion, training allowances, or job security

- Provisions for recall or reinstatement once conditions improve

This approach reflects a shared commitment to continuity, balancing organizational viability with employee welfare.

SOURCES OF CONFLICT

Some situations generate more conflict than others. Anticipating these situations helps managers and employees prevent, manage, or resolve conflicts effectively. Sources of conflict arise from internal processes within organizations and from broader external socio-economic and political conditions.

Internal sources

Internal causes of workplace conflict include incompatible personality or value systems, unclear or overlapping job boundaries, competition for limited resources, intergroup rivalry, ineffective communication, task interdependence, organizational complexity, ambiguous policies or standards, unreasonable deadlines and targets, unmet expectations (for example, pay or promotion), and unresolved or suppressed disputes (Filley, 1975). These factors do not always cause overt conflict but shape expectations and working conditions in ways that increase the likelihood of disputes.

External sources

External, contextual sources of conflict vary by country and industry. In Nigeria, for example, conflict can stem from government industrial and economic policies, poor macroeconomic management, shortcomings in labour legislation, unpatriotic behaviour among political and business elites, and unequal distribution of wealth and power. These broader forces affect organizational stability, employee morale, and labor–management relations.

Four basic classifications of conflict antecedents

When examined closely, most conflict antecedents fall into four broad categories—personality, value, intergroup, and cross-cultural conflicts—each with distinct implications for workplace harmony.

- Personality conflict

Personality conflict is interpersonal opposition driven by personal dislike, incompatible dispositions, or chronic interpersonal friction. A person’s personality—stable traits and habitual responses—shapes how they think, feel, and behave, and therefore whether they are more prone to cooperate or to clash with others. Workplace incivility often seeds personality conflict. Small, everyday irritations (for example, curt replies on the phone, failing to say “please” or “thank you,” hovering over a colleague’s desk, dropping trash, or ignoring customary greetings) can escalate depending on individuals’ temperaments, prior experiences, and relative status. - Value conflict

Values are enduring beliefs about preferred ways of behaving or desirable end-states (Rokeach, 1973). Because values are deeply held and usually formed early in life, clashes over values can be particularly entrenched. Value conflict appears in three main forms:

- Intrapersonal value conflict: Competing internal values or priorities create stress and role conflict (for example, a person who values harmony but works in a highly competitive setting).

- Interpersonal value conflict: Differences in values between individuals give rise to disagreement (for example, an employee who refuses to engage in corrupt practices while colleagues tolerate or profit from them).

- Individual–organization value conflict: Conflict emerges when organizational values or practices conflict with employees’ personal values. Even well-intentioned corporate values (such as strict punctuality, particular norms of respect, or diversity policies) can be difficult to implement in a heterogeneous workforce where those values are assimilated to different degrees.

Cross-cultural conflict

In an increasingly global economy—characterized by joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, foreign direct investment, and cross-border partnerships—cultural differences frequently produce friction. Differences in time orientation, personal space, language, religion, and notions of achievement can lead to misunderstandings and disagreements. Accommodation, cultural adaptation, and clear cross-cultural communication are essential to managing these differences. Note that cultural differences are not matters of right or wrong but require deliberate strategies for integration and cooperation.

Intergroup conflict

Intergroup conflict occurs between work groups, teams, departments, or unions. It can take the form of competition for resources, turf battles, politicking, or coordinated industrial action, and it poses a direct threat to productivity and organizational performance if left unchecked.

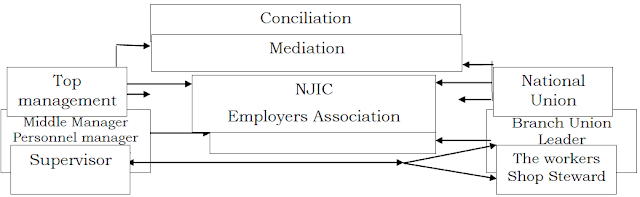

CONFLICT HANDLING MECHANISM

Resolving conflicts revolves

around the use ofinternalandexternalmechanisms. Internal mechanisms

are those put in place by the organisation based on its experiences of past

disputes and attempts at dispute resolution.

The internal mechanism, as articulated by Obisi (1996), arises when management systematically devises methods to regulate overt conflict. The resulting attempts and mechanisms are frequently termed as internal conflict regulatory machinery. Essentially, the external methods of conflict resolution are employed only after the internal procedures have reached a deadlock. The internal procedures are delineated as follows:

Source: Animashaun and Shabi (2000), adapted.

The table shows the progression of action often taken internally the moment grievance is noted. The worker reports to his/her supervisor or the head of section, whichever is more accessible. If these could not resolve the conflict, it is reported to the human resource manager and or union leader who will try to resolve the dispute. If no satisfactory resolution is obtained, the case may be taken to the head of department who may attempt resolution or eventually refer the matter to the grievance committee.

External dispute resolution mechanisms.

When workplace or industrial disputes cannot be resolved internally, external mechanisms are employed to ensure fairness, justice, and long-term stability. These methods are formalized in law and involve neutral third parties or judicial bodies.

1. 🕊️ Mediation

According to Subsection 3 of the Trade Disputes Decree (1976), parties in conflict should seek the assistance of a mutually agreed mediator within seven days.

- The mediator facilitates dialogue and helps the parties identify solutions.

- Mediation is voluntary and relies on cooperation, making it suitable for disputes where trust can be rebuilt.

2. 🤝 Conciliation

If mediation fails, the Minister of Labour appoints a conciliator within seven days. The conciliator must submit a report within 14 days.

- The conciliator’s role is to encourage settlement and propose solutions.

- If both parties agree, the conciliator may finalize the resolution.

- Conciliation is more formal than mediation but still emphasizes voluntary agreement.

3. ⚖️ Industrial Arbitration Panel (IAP)

When conciliation fails, the dispute is referred to the Industrial Arbitration Panel (IAP) under Section 7 of the Trade Disputes Decree.

- The IAP is composed of trade union representatives, employers, and respected administrators.

- It functions like a court and can hear cases—including those involving essential services—directly, bypassing earlier stages.

- Cases are typically heard within 42 days, though the Minister of Labour may extend this period if necessary.

- The IAP’s decision (award) is submitted to the Minister of Labour and communicated to the parties.

- If no objection is raised within 21 days of publication, the award becomes binding.

- If objections are raised, the matter is referred to the final authority.

4. 🏛️ National Industrial Court

The National Industrial Court (NIC) is the highest authority in industrial dispute resolution.

The NIC’s awards are legally enforceable, and parties who fail to comply may be held in contempt of court.

It is equivalent to a High Court and may act as a Court of Appeal or a Court of First Instance.

Certain cases, particularly those involving essential services, can be referred directly to the NIC.

The court interprets collective agreements and reviews decisions of lower dispute-resolution bodies.

It is composed of five members, chaired by a serving or retired High Court judge.

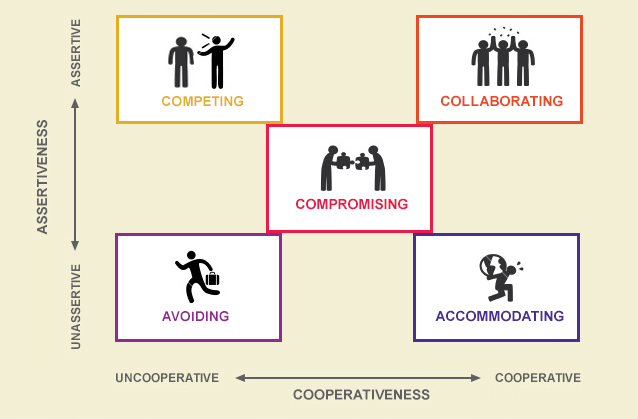

NEGOTIATION/CONFLICT HANDLING STRATEGIES

According to Bankole (2011), conflict handling behaviour refers to the behavioural orientation an individual adopts in conflict situations. This orientation determines the style or strategy used to resolve disputes. Mitchell (2002) identifies five major conflict-handling strategies:

1. 💪 Dominating Strategy

- Relies heavily on position, power, aggression, and verbal dominance.

- The primary goal is a win–lose outcome, where the needs of the other party are ignored.

- Effective when power is uneven, but often leads to alienation, resentment, and future grievances.

- May precipitate deadlocks and recurring disputes.

2. 🤝 Accommodating Strategy

- Produces a lose–win outcome, prioritizing the needs of others over self.

- Differences and divergent opinions are downplayed, while common interests are emphasized.

- Demonstrates high concern for others but low concern for self.

- Useful for maintaining harmony, though it may sacrifice personal goals.

3. 🚫 Avoiding Strategy

- Results in a lose–lose situation, as both parties withdraw from resolution processes.

- Common tactics include postponement, avoidance of topical issues, jokes, noncommittal attitudes, and irrelevant remarks.

- Ineffective in resolving disputes, often leaving parties frustrated, resentful, and dissatisfied.

- Typically delays resolution rather than addressing the root causes.

4. 🌍 Collaborative Strategy

- Focuses on problem-solving and cooperation, with high concern for both self and others.

- Involves identifying conflictual issues and generating creative, flexible solutions.

- Produces a win–win outcome, fostering inclusiveness, satisfaction, and long-term cordial relations.

- Considered the most constructive approach for sustainable conflict resolution.

5. ⚖️ Compromising Strategy

- Based on give-and-take or sharing, seeking a middle ground.

- Involves trading concessions to reach a mutually satisfactory outcome.

- Promotes balance between production, remuneration, and industrial peace.

- Effective in situations where neither party can achieve all their goals but both can gain partially.

In summary, these five strategies—dominating, accommodating, avoiding, collaborative, and compromising—represent different orientations toward conflict resolution. The choice of strategy depends on the context, power dynamics, and desired outcomes.

ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (ADR)

Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) refers to a range of external techniques designed to reduce tension and build trust between disputing parties. It provides a means of reaching agreement short of litigation and has gained widespread acceptance among both the general public and the legal profession in recent years.

Growing Importance of ADR

- In many countries, ADR has become an integral part of legal systems.

- Some courts now require parties to attempt ADR, usually mediation, before allowing cases to proceed to trial.

- Its rising popularity is explained by:

- Increasing caseloads in traditional courts

- Lower costs compared to litigation

- Preference for confidentiality

- Greater party control over the selection of neutral decision-makers

Advantages of ADR

ADR offers several benefits over traditional litigation, including:

- Suitability for multi-party disputes

- Flexibility of procedure – parties determine and control the process

- Efficiency – reduced time wastage and lower costs

- Simplicity – less complex than court proceedings

- Expertise – parties can choose a neutral third party with subject-matter knowledge

- Confidentiality – proceedings are private, protecting reputations and sensitive information

Outcomes of ADR

ADR often produces results that are more practical and durable than litigation. Key outcomes include:

- Faster and more likely settlements

- Solutions tailored to parties’ interests and needs rather than rigid legal rights

- Greater durability of agreements

- Preservation of relationships and reputations

✨ In summary, ADR is not only a cost-effective and flexible alternative to litigation but also a relationship-preserving mechanism that strengthens trust and cooperation between disputants.

A growing no of organisations now have formal ADR policies using various combination of techniques such as;

Facilitation:It is a form of detriangle in which the third party, usually a manager, informally bring disputants to deal directly with each other in a positive and constructive manner.

Conciliation: It used when conflicting parties refuse to meet face to face. A neutral third party acts as acommunicationconduit with immediate goal to establish direct communicationto explore common ground of understanding thereby resolving the dispute.

Peer review:A panel of trustworthy co-workers, selected (and rotated from time to time) for their objectivity and perhaps neutrality, hears both sides of the dispute issues in an informal and

confidential manner. The decision of the panel may or may not be binding on parties depending on company’s policy.

Ombudsman:A well respected and trusted employee may be engaged to hear out the parties

and to attempt a resolution of the dispute.

CONCLUSION

One could see that conflict though a part of organisational life can be anticipated and managed using both internal and external mechanisms. There are equally negotiation/bargaining strategies that are available to gain either cooperation or concessions in either win-win or win-lose situations. Recently the

Alternative Dispute Resolution is gaining in popularity because it is less legalistic, cheaper, less time-consuming and could achieve effective resolution of disputes if parties go into it in good faith.

References for further Reading

Jayeoba, F., Ayantunji, A., & Sholesi, O. (2013). Conflict and negotiation in organizations: The role of need-fulfilling agents. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 3(6), 45–56. Downloadable Article (Journal of Business & Social Research)

Dunlop, J. T. (1965). Industrial relations systems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Google Books | Internet Archive

Discover more from Decroly Education Centre - DEDUC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.