African Traditional Religion (ATR) constitutes the deeply rooted system of beliefs, practices, and institutions through which many African peoples understand the world, regulate social life, and relate to the non‑material dimensions of existence. Far from being a singular, uniform creed, ATR comprises a rich diversity of local traditions and cosmologies that share certain structural features: a belief in a transcendent reality, an active spirit world, specialized ritual practices, moral codes embedded in communal life, and cosmological narratives that confer meaning upon birth, death, misfortune, and success. As a social institution, ATR functions both to explain the cosmos and to sustain social cohesion, moral order, and cultural continuity.

Worldview and Core Beliefs in African Traditional Religion

Central to ATR is a worldview that unites the visible and invisible realms. Most traditions posit a supreme creative force—variously conceived as a distant Creator, High God, or Ultimate Reality—who is ultimately responsible for the origin of the universe. Alongside or beneath this supreme being operates a populous spirit world, populated by ancestral spirits, nature spirits, and other supernatural agents. Ancestors occupy a privileged place: they are the deceased members of a lineage who continue to influence the fortunes of the living. Through ritual propitiation, offerings, and moral comportment, the living seek the guidance and protection of ancestors and seek to avert malevolent spiritual forces.

This cosmology situates human beings within a network of reciprocal obligations. Life is not understood as autonomous individual agency alone but as embedded in kinship, community, and spiritual relationships. Misfortune—illness, drought, crop failure, or interpersonal conflict—is often interpreted in relational or moral terms, frequently as a disruption of harmony between humans, ancestors, and the spirit order. Restoring balance requires rites of reconciliation, cleansing, or divination to identify causes and prescribe corrective action.

Rituals, Practices, and Material Expressions

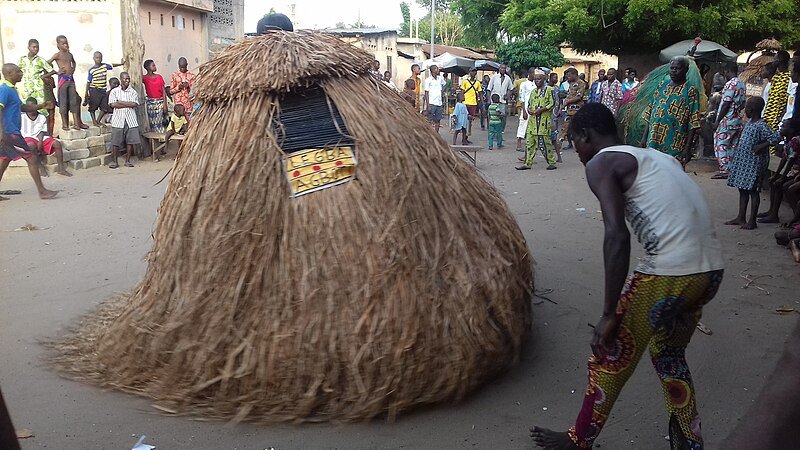

Rituals are the primary mode through which beliefs are transmitted, enacted, and experienced. Ceremonies mark critical life transitions—birth, naming, initiation, marriage, and death—and reinforce social identity and continuity. Festivals and communal rites reinforce shared history and cosmology, often incorporating music, dance, masks, and dramatic enactments of foundational myths. Divination and healing practices occupy central roles in addressing ambiguity and uncertainty; diviners mediate between clients and the spirit world to diagnose spiritual causes and recommend sacrifices, taboos, or remedial rites.

Material culture in ATR—statues, amulets, regalia, shrines, sacred groves, and specific architectural forms—serves as tangible loci of sacred presence and memory. Objects and places are invested with sacredness; they embody authority, mediate encounters with the divine, and function as mnemonic devices for communal values. Clothes, body adornment, and performance further materialize cosmological meanings and social status.

Ethics, Social Order, and the Role of Religion in Society

ATR undergirds ethical norms and social regulation. Moral injunctions—respect for elders, hospitality, reciprocity, truthfulness, and care for kin—are often framed as obligations to ancestors and to the community. Religious sanctions and rites reinforce these norms; transgressions are not merely social infractions but disruptions of spiritual order, which may attract corrective rituals or restorative justice measures. Religious institutions thus serve as mechanisms for conflict resolution, social integration, and the transmission of cultural memory.

In many African societies ATR functions as the cohesive factor that fosters harmony and collective identity. Religious specialists—priests, diviners, healers, ritual elders, and custodians of sacred knowledge—play essential roles in maintaining social equilibrium. They preside over rites, administer sacrificial offerings, interpret omens, and guide communal responses to crises. Leadership within ATR is frequently embedded in kinship and age‑grade structures, reinforcing reciprocal duties across generations.

Knowledge Transmission and Education

Transmission of ATR is predominantly informal and communal. Children learn cosmology, proverbs, myths, taboos, and ritual competence through participation, storytelling, observation, and apprenticeship with elders. Central narratives and myths are retold and performed across generations, enabling continuity while allowing for local adaptation. Initiation rites and formal apprenticeships institutionalize specialized knowledge and integrate youth into social and spiritual responsibilities.

Sacred Time and Space

ATR organizes time and space in ways that integrate cosmology and social life. Sacred calendars, agricultural cycles, and periodic festivals frame communal activity. Certain locations—shrines, groves, rivers, mountains, and shrines—are set apart as embodiments of the sacred and as sites for encounter with spiritual forces. Spatial and temporal demarcations distinguish the sacred from the profane, guiding individual and collective conduct.

Interaction with Other Religions and Modernity

ATR has not remained isolated from other world religions. Islam and Christianity have long interacted with traditional African beliefs, resulting in complex patterns of syncretism, adaptation, resistance, and negotiation. In many communities, people may simultaneously draw upon ATR resources and the practices of world religions to address different existential needs. Colonialism, missionary activity, urbanization, formal education, and the forces of globalization have transformed ATR’s public expressions and institutional contexts. Nevertheless, elements of ATR persist—often reconfigured—in contemporary African religiosity, social practice, and political life.

Contemporary Significance and Challenges

African Traditional Religion continues to shape ethical frameworks, cultural identity, and communal solidarity. Its practices inform approaches to health, conflict resolution, environmental stewardship, and rites of passage. At the same time, ATR faces challenges: marginalization and stigmatization by adherents of global religions and secular institutions, loss of ritual specialists and sacred knowledge due to migration and modernization, and the commodification or misrepresentation of practices for tourism or popular culture.

Scholarly Perspectives and Methodological Considerations

Scholars such as John S. Mbiti have framed ATR as a comprehensive system that permeates social life, identifying its dimensions as belief, practice, sacred objects and places, values and morals, and religious officials. Contemporary anthropology and religious studies emphasize the plurality and historicity of ATR, cautioning against essentializing or static portrayals. Methodologically, researchers foreground emic perspectives—how practitioners themselves articulate meanings—while situating practices within historical change and power relations. Comparative approaches illuminate both convergences across African religious traditions and the distinctiveness of local systems.

Conclusion

African Traditional Religion is a dynamic, multifaceted complex of beliefs and practices that grounds social life, confers meaning, and mediates relations between the human and the non‑human. Rooted in communal experience, transmitted through ritual and narrative, and embodied in sacred spaces and objects, ATR continues to play a vital role in many African societies. Its study invites careful attention to diversity, continuity, and change, and to the ways religious imagination informs ethical life, social cohesion, and cultural resilience.

Discover more from Decroly Education Centre - DEDUC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.