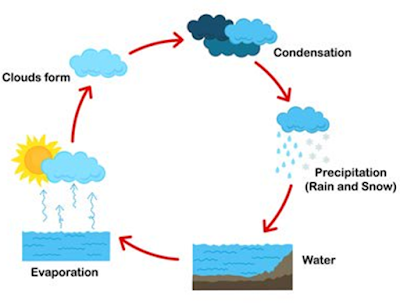

The water cycle, or hydrologic cycle, constitutes one of the Earth’s most fundamental and pervasive natural systems. It governs the continuous movement of water within the atmosphere, across the terrestrial surface, through the biosphere, and into the lithosphere and hydrosphere. Although the cycle comprises numerous interrelated processes and complex interactions, it can be usefully conceptualized in terms of five principal elements: evaporation, condensation, precipitation, infiltration (including percolation and groundwater flow), and surface runoff (including collection).

Presenting the water cycle in this simplified five-element framework facilitates comprehension while preserving the essential dynamics that maintain climatic balance, support ecosystems, and sustain human societies. The purpose of this article is to examine each of these five elements in depth—describing mechanisms, significance, and interconnections—while also considering anthropogenic influences and broader environmental implications.

Evaporation

Mechanism and Drivers

Evaporation is the process by which liquid water is transformed into water vapour and transferred from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere. It primarily occurs from open water bodies—oceans, lakes, rivers—and from moist soil surfaces. Solar radiation, the principal energy source for evaporation, heats the surface layer of water, increasing molecular kinetic energy until molecules escape into the air as vapor. Other drivers include air temperature, humidity gradients (vapor pressure deficit), wind speed (which removes saturated air and enhances flux), and surface area exposure.

Significance

Evaporation is the principal pathway by which terrestrial and aquatic reservoirs communicate with the atmosphere. Over the oceanic expanses, evaporation supplies the atmosphere with the bulk of atmospheric moisture that eventually precipitates elsewhere; hence, this process is central to global energy redistribution and climatic patterns. Evaporation also exerts a cooling effect on surfaces, as latent heat is consumed during the phase change, thereby influencing local and regional thermal regimes.

Interconnections and Variability

Evaporation rates vary with latitude, season, and surface characteristics. For example, arid regions with high insolation and low humidity can experience substantial evaporative losses, whereas equatorial regions with abundant moisture may see high evaporation that is often balanced by immediate condensation. Vegetation mediates evaporation through transpiration—a companion process—collectively termed evapotranspiration, which links biological activity with atmospheric moisture dynamics.

Condensation

Mechanism and Drivers

Condensation is the transformation of water vapor into liquid water droplets or ice crystals when the air becomes saturated or when vapor encounters surfaces cooler than the dew point. This process frequently occurs on aerosol particles (condensation nuclei) in the atmosphere, where minute droplets coalesce to form clouds and fog. Temperature reduction (adiabatic cooling during ascent), increases in relative humidity through mixing, and the presence of condensation nuclei are key facilitators of condensation.

Significance

Condensation organizes atmospheric moisture into structures—clouds—that are essential for modulating planetary albedo, acting as agents of radiative forcing, and serving as precursors to precipitation. Moreover, cloud processes substantially influence weather patterns and the distribution of solar and terrestrial radiation, exerting feedbacks on surface temperatures and hydrologic redistribution.

Interconnections and Variability

Cloud microphysics—droplet formation, growth by collision-coalescence, and ice-phase mechanisms—determine whether condensed moisture will remain airborne as cloud or progress toward precipitation. Anthropogenic aerosols can alter condensation dynamics by modifying the abundance and properties of cloud condensation nuclei, thereby affecting cloud reflectivity and precipitation patterns.

Precipitation

Mechanism and Drivers

Precipitation encompasses the fall of condensed water—from clouds to the surface—in forms including rain, snow, sleet, hail, and drizzle. The initiation of precipitation depends on cloud microphysics and atmospheric dynamics: droplets or ice crystals must grow sufficiently large to overcome updrafts and air resistance. Processes such as collision-coalescence in warm clouds and the Bergeron–Findeisen mechanism in mixed-phase clouds are central to droplet and crystal growth. Large-scale drivers include frontal systems, convective uplift, orographic forcing, and tropical cyclones, each producing distinctive precipitation regimes.

Significance

Precipitation is the principal mechanism by which atmospheric water is returned to the surface, replenishing freshwater resources, maintaining river flow, sustaining terrestrial ecosystems, and recharging groundwater. Its spatial and temporal patterns define climate zones, influence agricultural productivity, and determine water availability for human consumption and industry.

Interconnections and Variability

Precipitation exhibits substantial variability across spatial and temporal scales. Orographic precipitation concentrates moisture on windward slopes, creating rain shadows on leeward sides. Seasonal patterns (monsoons, wet and dry seasons) emerge from differential heating and atmospheric circulation. Human alterations—such as urban heat islands or emissions affecting cloud condensation nuclei—can alter local precipitation patterns.

Infiltration, Percolation, and Groundwater Flow

Mechanism and Drivers

Infiltration refers to the movement of water from the surface into the soil matrix. Percolation describes the downward movement of infiltrated water through soil and porous rock toward saturated zones. When percolated water reaches impermeable strata, it accumulates to form groundwater reservoirs within aquifers. Groundwater flow is governed by hydraulic gradients and aquifer properties such as porosity and permeability.

Significance

The subsurface compartment of the water cycle serves as a buffered storage system, modulating surface water availability and providing sustained baseflow to rivers and springs during dry intervals. Groundwater supports agriculture (irrigation), municipal water supplies, and ecosystems dependent on consistent moisture. Furthermore, aquifers can store water over long timescales, acting as a critical resource during periods of surface scarcity.

Interconnections and Variability

Infiltration rates depend on soil texture, land cover, antecedent moisture conditions, and land use. Urbanization with impervious surfaces reduces infiltration and increases runoff, altering the balance between surface and subsurface flows. Overextraction of groundwater can lower water tables, induce land subsidence, and reduce baseflow to surface waters. Conversely, managed aquifer recharge and land management practices can enhance infiltration and restore subsurface reservoirs.

Surface Runoff and Collection

Mechanism and Drivers

Surface runoff is the portion of precipitation that flows over land toward rivers, lakes, and oceans, rather than infiltrating into the ground. Runoff mechanisms include interflow (shallow subsurface lateral flow) and overland flow, initiated when rainfall intensity exceeds infiltration capacity or when soil becomes saturated. Collection refers to the concentration of runoff into channels and basins, eventually conveying water to larger water bodies.

Significance

Runoff is vital for transporting water, sediment, nutrients, and dissolved materials across the landscape. It sculpts landforms through erosion and deposition, sustains fluvial ecosystems, and supplies reservoirs and rivers that humans depend upon for water, energy (hydropower), and transportation. The timing and magnitude of runoff events also determine flood risk and water management challenges.

Interconnections and Variability

Runoff is sensitive to land cover, topography, soil saturation, and weather intensity. Deforestation, agriculture, and urbanization typically increase runoff and accelerate peak flows, raising flood potential and reducing groundwater recharge. Conversely, conservation practices—such as riparian buffers, wetlands restoration, and permeable surface design—attenuate runoff, enhance water quality, and promote collection that benefits storage and ecological integrity.

Synthesis and Systemic Interactions

The five elements described—evaporation, condensation, precipitation, infiltration/groundwater flow, and surface runoff/collection—operate as an integrated system whose dynamics are governed by energy flows, thermodynamics, and material transport. These elements are not independent; rather, they constitute a set of feedback loops. For instance, increased evaporation augments atmospheric moisture, potentially intensifying precipitation downwind; enhanced precipitation may increase infiltration and recharge aquifers, altering baseflows and moderating river discharge.

Vegetation mediates multiple elements through transpiration (linking biological processes to evaporation), root-mediated infiltration, and interception of precipitation. Climatic factors—temperature, atmospheric circulation patterns, and anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations—influence all elements, altering the balance and spatial distribution of water resources.

Human Influence and Management Implications

Human activities profoundly modify the water cycle at local to global scales. Urbanization changes surface permeability and runoff regimes; agriculture extracts and redistributes water and can alter evaporative fluxes; industrial emissions and land-use changes influence cloud properties and precipitation. Climate change—driven by increased greenhouse gas concentrations—modifies evaporation and precipitation patterns, intensifies the hydrologic cycle in some regions, and exacerbates droughts and floods in others.

Consequently, effective water resource management requires understanding the five elemental processes, integrating them into planning for sustainable supply, flood mitigation, land-use policy, and ecosystem conservation. Strategies such as watershed management, sustainable groundwater extraction, restoration of wetlands, afforestation, and adoption of green infrastructure can mitigate adverse effects and harness natural processes to maintain hydrologic balance.

Conclusion

Reducing the complexity of the hydrologic cycle to five principal elements—evaporation, condensation, precipitation, infiltration and groundwater flow, and surface runoff and collection—offers a clear and coherent framework for understanding water’s continuous movement across Earth’s systems. Each element embodies distinct physical processes and carries particular significance for climate regulation, ecosystem health, and human welfare. Their interactions underpin water availability and distribution, while human activities and global change increasingly perturb these relationships. Appreciating the roles and interdependencies of these five elements is therefore essential for informed environmental stewardship, resilient infrastructure, and adaptive responses to emerging hydrologic challenges.

Discover more from Decroly Education Centre - DEDUC

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.